(Q&A Clarify Version)

Q: Are high sample rates mean better audio quality?

A: Not always true. unless you have 3,500$+ HDX Converter

Q: How is that possible?

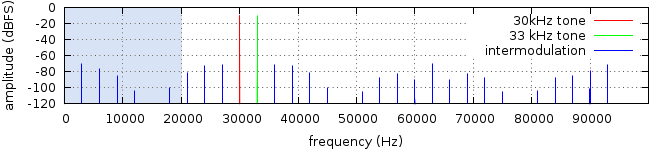

A: In The Nutshell. Many “affordable” soundcards have a non-linear response to high frequency content. Meaning that even though they are technically capable of recording at 96 kHz and above, the small benefits of the higher sample rate are completely outweighed by unwanted “inter-modulation distortion” in the analogue stages.

Q: What’s the point of high sample rates anyway ?

A: The sample rate determines how many samples per second a digital audio system uses to record the audio signal. The higher the sample rate, the higher frequencies a system can record. CDs, most mp3s and the AAC files sold by the iTunes store all use a sample rate of 44.1 kHz, which means they can reproduce frequencies up to roughly 20 kHz.

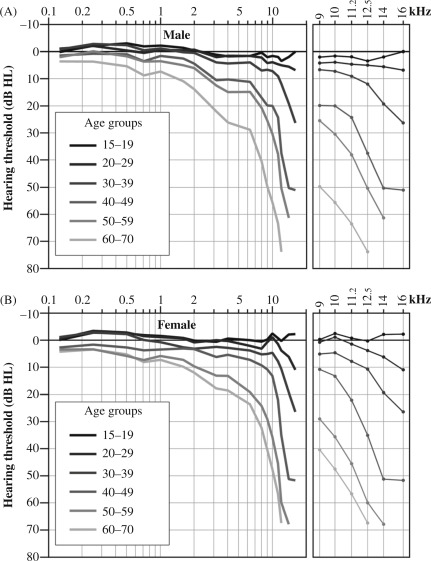

A: Testing shows that most adults can’t hear much above 16 kHz, so on the face of it, this seems sensible enough. Some can, but not the majority. And examples of people who can hear above 20 kHz are few and far between. And to accurately reproduce everything below 20 kHz, a digital audio system removes everything above 20 kHz – this is the job of the anti-aliasing filter.

A: But a fair few musical instruments produce sound well above these frequencies – muted trumpet and percussion instruments like cymbals or chime bars are clear examples. This leads to two potential objections to a 44.1 kHz sample rate – first, that in order to reproduce a sound accurately we should capture as much of it as possible, including frequencies we probably can’t hear. There are various suggestions that we may be able to somehow perceive these sounds, even if we can’t actually hear them. And secondly that depending on the design, the anti-aliasing filter may have an effect at frequencies well below the 20 kHz cut-off point.

Q: So why NOT use higher sample rates, then ? Back when CD was released, recording at 96 kHz or above simply wasn’t viable at a reasonable price, especially not in consumer audio. Times have moved on though, and these days almost any off-the-peg digital audio chip is capable of at least 96 kHz processing, if not higher.

Q: Now these files take up much more space than simple 44.1 kHz audio, but hard drive space is cheap, and getting cheaper all the time – why not record at 96 kHz or higher, just in case either of those hotly debated arguments really does carry some weight ?

A: The answer lies in the analogue circuitry of the equipment we use. Just because the digital hardware in an interface is capable of 96 kHz or higher audio processing, doesn’t mean the analogue stages will record or play the signal cleanly. It’s quite common for ultrasonic content to cause inter-modulation distortion right down into the audible range. Or in simple English, the inaudible high-frequency content actually makes the audio you can hear sound worse.

Q&A controversial question

Finally, the fact that ultrasonic content can potentially cause inter-modulation distortion and make things sound different even when they shouldn’t raises a tough question. Are all the people who claim to be hearing improved quality at 96 kHz and above really hearing what they think they are ? Or are they just hearing inter-modulation distortion ?

Summary

Maybe 48 kHz sample rate is actually good enough ?

"maybe yes & maybe not" everything it's come down to....

What's your project you're working with?

Sound design, organic orchestra, audiophile jazz, classical, world music and send it to the studios or you having HD system?

Then, Yes 96kHz is better, Because Film and TV Broadcasting often require that recordings be at a much higher sample rate (even higher than 96kHz sometime)

Nah I just do collab, create music and fun stuff.

Working at high sample rate, is quite a lot of hassle, Exporting x4 time more data, CPU need to work x10 time harder.

If you gain very little to nothing from it. Why create the hassle in the first place?

Read more about this: web archive

Q: Are high sample rates mean better audio quality?

A: Not always true. unless you have 3,500$+ HDX Converter

Q: How is that possible?

A: In The Nutshell. Many “affordable” soundcards have a non-linear response to high frequency content. Meaning that even though they are technically capable of recording at 96 kHz and above, the small benefits of the higher sample rate are completely outweighed by unwanted “inter-modulation distortion” in the analogue stages.

Q: What’s the point of high sample rates anyway ?

A: The sample rate determines how many samples per second a digital audio system uses to record the audio signal. The higher the sample rate, the higher frequencies a system can record. CDs, most mp3s and the AAC files sold by the iTunes store all use a sample rate of 44.1 kHz, which means they can reproduce frequencies up to roughly 20 kHz.

A: Testing shows that most adults can’t hear much above 16 kHz, so on the face of it, this seems sensible enough. Some can, but not the majority. And examples of people who can hear above 20 kHz are few and far between. And to accurately reproduce everything below 20 kHz, a digital audio system removes everything above 20 kHz – this is the job of the anti-aliasing filter.

A: But a fair few musical instruments produce sound well above these frequencies – muted trumpet and percussion instruments like cymbals or chime bars are clear examples. This leads to two potential objections to a 44.1 kHz sample rate – first, that in order to reproduce a sound accurately we should capture as much of it as possible, including frequencies we probably can’t hear. There are various suggestions that we may be able to somehow perceive these sounds, even if we can’t actually hear them. And secondly that depending on the design, the anti-aliasing filter may have an effect at frequencies well below the 20 kHz cut-off point.

Q: So why NOT use higher sample rates, then ? Back when CD was released, recording at 96 kHz or above simply wasn’t viable at a reasonable price, especially not in consumer audio. Times have moved on though, and these days almost any off-the-peg digital audio chip is capable of at least 96 kHz processing, if not higher.

Q: Now these files take up much more space than simple 44.1 kHz audio, but hard drive space is cheap, and getting cheaper all the time – why not record at 96 kHz or higher, just in case either of those hotly debated arguments really does carry some weight ?

A: The answer lies in the analogue circuitry of the equipment we use. Just because the digital hardware in an interface is capable of 96 kHz or higher audio processing, doesn’t mean the analogue stages will record or play the signal cleanly. It’s quite common for ultrasonic content to cause inter-modulation distortion right down into the audible range. Or in simple English, the inaudible high-frequency content actually makes the audio you can hear sound worse.

Q&A controversial question

Finally, the fact that ultrasonic content can potentially cause inter-modulation distortion and make things sound different even when they shouldn’t raises a tough question. Are all the people who claim to be hearing improved quality at 96 kHz and above really hearing what they think they are ? Or are they just hearing inter-modulation distortion ?

Summary

Maybe 48 kHz sample rate is actually good enough ?

"maybe yes & maybe not" everything it's come down to....

What's your project you're working with?

Sound design, organic orchestra, audiophile jazz, classical, world music and send it to the studios or you having HD system?

Then, Yes 96kHz is better, Because Film and TV Broadcasting often require that recordings be at a much higher sample rate (even higher than 96kHz sometime)

Nah I just do collab, create music and fun stuff.

Working at high sample rate, is quite a lot of hassle, Exporting x4 time more data, CPU need to work x10 time harder.

If you gain very little to nothing from it. Why create the hassle in the first place?

Read more about this: web archive

(Experiments article)

I do this experiment for around 3-4 years ago, back in the day i only have cubase 5 and Adobe Audition 1.5

Ah shit, here we go again.

To Be Honest, I'm so tired of this endless DAW of WARS, That has been around over decade.

If you’ve found yourself caught up on forums arguing the toss about which DAW sounds best, then start watching videos of kittens licking their balls, it’s a better waste of time.

The Underlying Math and Audio Quality Aspect of DAWs

Fundamentally, DAWs are calculators at heart. They take multiple audio streams, add them together, and give you the results via your monitors or a bounced audio file.

Long Story Short

In the past audio engines used fewer bits for calculating math operations for all digital signal processing and sound generation. However nowadays software companies need to use the highest practically possible bit depth to stay current, which is 64-bit float. (my obsolete Cubase 5 run at 32-bit floating point)

However, some producers - including experienced audio professionals who you'd like to imagine know better - for some reason think they run on voodoo or some other arcane art.

Basic Thinking

My suspicion and thinking is that basically all the latest DAW programs are the same in basic mixing capabilities.

Maybe if there is some difference it should be so minimal that it can't be heard or only in phase cancellation tests or maybe less than -70 to -90 decibels. So I'll explore this topic.

Material for Testing

I used these render settings:

I set out to find the difference of the mixing engines.

First, I rendered the multi-tracks in Cubase 5, Reason 5, Pro Tools 10, Cakewalk Sonar, Studio one 4, Reaper 6 and then made a phase cancellation test in Audacity. The cancellation was perfect so there were no differences, result in silent sound.

Conclusion

There are no differences when:

You can do this experiment successfully, just be honest to yourself.

Read more about it: DAW wars

I do this experiment for around 3-4 years ago, back in the day i only have cubase 5 and Adobe Audition 1.5

Ah shit, here we go again.

To Be Honest, I'm so tired of this endless DAW of WARS, That has been around over decade.

If you’ve found yourself caught up on forums arguing the toss about which DAW sounds best, then start watching videos of kittens licking their balls, it’s a better waste of time.

The Underlying Math and Audio Quality Aspect of DAWs

Fundamentally, DAWs are calculators at heart. They take multiple audio streams, add them together, and give you the results via your monitors or a bounced audio file.

Long Story Short

In the past audio engines used fewer bits for calculating math operations for all digital signal processing and sound generation. However nowadays software companies need to use the highest practically possible bit depth to stay current, which is 64-bit float. (my obsolete Cubase 5 run at 32-bit floating point)

However, some producers - including experienced audio professionals who you'd like to imagine know better - for some reason think they run on voodoo or some other arcane art.

Basic Thinking

My suspicion and thinking is that basically all the latest DAW programs are the same in basic mixing capabilities.

Maybe if there is some difference it should be so minimal that it can't be heard or only in phase cancellation tests or maybe less than -70 to -90 decibels. So I'll explore this topic.

Material for Testing

- Microsoft Windows 7 (64-bit), Mac OS Version 10.6: Snow Leopard

- Cubase 5 (32-bit)

- Reason 5 (32-bit)

- Pro Tools 10 (32-bit)

- Cakewalk Sonar (64-bit)

- Studio one 4 (64-bit)

- Reaper 6 (64-bit)

- Audacity 2.0.6 (32-bit)

- My finish multi-tracks session 66 tracks (24/48kHz)

Note:- no plugins on master buss

- no plugins on Audio channels

- default volume 0 dB or Unity Gain on all the channels

- no automation

- stereo pan law: equal power

I used these render settings:

- output: master output

- file type: WAV

- sample rate: 44.1 kHz

- bit depth: 24 bit

- dither options: no dithering

I set out to find the difference of the mixing engines.

First, I rendered the multi-tracks in Cubase 5, Reason 5, Pro Tools 10, Cakewalk Sonar, Studio one 4, Reaper 6 and then made a phase cancellation test in Audacity. The cancellation was perfect so there were no differences, result in silent sound.

Conclusion

There are no differences when:

- no stock plugins used

- no automation used

- no warping used

- no different stereo pan law

- stock plugins used

- automation used

- different warping used

- different stereo pan law

You can do this experiment successfully, just be honest to yourself.

Read more about it: DAW wars

(Q&A Clarify Version)

"Unfortunately, when you do trust your ears, you're not just trusting your ears"

Q: Trust your ears guide is actually helpful?

A: In my personal experience, Advice like this is undoubtedly the most common and unhelpful piece of non-advice you'll find online is 'trust your ears', which is trotted out with tedious regularity by people who don't actually have a useful answer to your question.

Q: Can I truly trust my ears?

A: One of the absolute most frustrating things about audio production is that you simply can’t trust your ears. The human ear is not a very reliable tool for knowing if your tracks are sounding great or not, plain and simple. Our ears adjust, and our brains compensate for things we’re hearing and very quickly we lose perspective on just what exactly our audio is sounding like.

If you read my Audio myths-busting series you know that most adults can’t hear much above 16 kHz, People will lose their ability to detect higher frequencies as you get older, can be affected by conditions such as having a cold or earwax buildup, and suffer from fatigue - but also your audio interface, monitor quality and positioning, and the shape and material of your room and everything in it. This seems sensible enough.

Myself learning this the hard way... it's very depressing if you're not get used to it. But it just the way it is, This is how human brain work. Accept it and working around them.

The hearing not only affect by age, also affect by gender, the shape of ear canal , the size ear drum, etc.

Q: If i can't trust my ear, what i can do?

A: One of the best things you can do to reset your ears is to play your mix through a very different set of speakers, cheap earbud, laptop speakers or even your phone.

Try it again with some headphones. Your ears will be fresh to the way your cans sound. But of course after a minute (or less) they will get used to that sound and you’ll lose some perspective. By switching speakers (even to cheap speakers) you force your ears to “wake up” and start paying close attention to the frequency balance. This state of resetting is so helpful in giving you information you need to make sure your mix is where you want it to be, and you don’t have to spend a lot of money either. Just listen to your mix on something other than your main speakers every now and then, and you’ll be better off for it.

A: Reference tracks is very handy when it come to checking the mix, By simply opening up a pro mix and listening to that for a minute, we can quickly regain perspective on what does sound good and how the mix is represented on our system.

A: In my experience. listen at lower volumes does help immensely. When we turn up audio our ears over emphasize the high and low frequencies, somewhat resembling what stereos do to make your music sound “better” and more “exciting.” That being said, it can be very misleading if you only mix at loud volumes. You think your mix is sound so good, but when it’s played back at a moderate to quiet volume everything falls apart. The solution is mix a much quieter volume. Of course, it’s always good to play back your mixes at a few different volume levels to gain perspective (because remember, you can’t trust your ears), but in general keep it low when you mix.

Q: Psycho-acoustic are real?

A: Yes. The Psycho-acoustic, sound perception is real, this is how humans perceive various of sounds. The human ear can nominally hear sounds in the range 20 Hz (0.02 kHz) to 20,000 Hz (20 kHz), this is our limits of perception. The upper limit tends to decrease with age; most adults are unable to hear above 16 kHz. The lowest frequency that has been identified as a musical tone is 12 Hz under ideal laboratory conditions. Tones between 4 and 16 Hz can be perceived via the body's sense of touch.

Conclusions (If you read all of this, Please don't take everything too serious)

This is why professional studios are designed by acousticians, treated with specialised materials, and use high-end monitors and visual analysis tools.

My advice.

Trust your ears, but only up to a point. Rest them, use reference tracks, check your mixdowns on as many reproduction systems as possible, and grab your trustworthy spectral analyser to keep an eye on those hard to monitor bass tones and rogue ringing frequencies.

If you don't have one, take a look here: My recommendation Plugins for Audio Production

"Unfortunately, when you do trust your ears, you're not just trusting your ears"

Q: Trust your ears guide is actually helpful?

A: In my personal experience, Advice like this is undoubtedly the most common and unhelpful piece of non-advice you'll find online is 'trust your ears', which is trotted out with tedious regularity by people who don't actually have a useful answer to your question.

Q: Can I truly trust my ears?

A: One of the absolute most frustrating things about audio production is that you simply can’t trust your ears. The human ear is not a very reliable tool for knowing if your tracks are sounding great or not, plain and simple. Our ears adjust, and our brains compensate for things we’re hearing and very quickly we lose perspective on just what exactly our audio is sounding like.

If you read my Audio myths-busting series you know that most adults can’t hear much above 16 kHz, People will lose their ability to detect higher frequencies as you get older, can be affected by conditions such as having a cold or earwax buildup, and suffer from fatigue - but also your audio interface, monitor quality and positioning, and the shape and material of your room and everything in it. This seems sensible enough.

Myself learning this the hard way... it's very depressing if you're not get used to it. But it just the way it is, This is how human brain work. Accept it and working around them.

The hearing not only affect by age, also affect by gender, the shape of ear canal , the size ear drum, etc.

Q: If i can't trust my ear, what i can do?

A: One of the best things you can do to reset your ears is to play your mix through a very different set of speakers, cheap earbud, laptop speakers or even your phone.

Try it again with some headphones. Your ears will be fresh to the way your cans sound. But of course after a minute (or less) they will get used to that sound and you’ll lose some perspective. By switching speakers (even to cheap speakers) you force your ears to “wake up” and start paying close attention to the frequency balance. This state of resetting is so helpful in giving you information you need to make sure your mix is where you want it to be, and you don’t have to spend a lot of money either. Just listen to your mix on something other than your main speakers every now and then, and you’ll be better off for it.

A: Reference tracks is very handy when it come to checking the mix, By simply opening up a pro mix and listening to that for a minute, we can quickly regain perspective on what does sound good and how the mix is represented on our system.

A: In my experience. listen at lower volumes does help immensely. When we turn up audio our ears over emphasize the high and low frequencies, somewhat resembling what stereos do to make your music sound “better” and more “exciting.” That being said, it can be very misleading if you only mix at loud volumes. You think your mix is sound so good, but when it’s played back at a moderate to quiet volume everything falls apart. The solution is mix a much quieter volume. Of course, it’s always good to play back your mixes at a few different volume levels to gain perspective (because remember, you can’t trust your ears), but in general keep it low when you mix.

Q: Psycho-acoustic are real?

A: Yes. The Psycho-acoustic, sound perception is real, this is how humans perceive various of sounds. The human ear can nominally hear sounds in the range 20 Hz (0.02 kHz) to 20,000 Hz (20 kHz), this is our limits of perception. The upper limit tends to decrease with age; most adults are unable to hear above 16 kHz. The lowest frequency that has been identified as a musical tone is 12 Hz under ideal laboratory conditions. Tones between 4 and 16 Hz can be perceived via the body's sense of touch.

Conclusions (If you read all of this, Please don't take everything too serious)

This is why professional studios are designed by acousticians, treated with specialised materials, and use high-end monitors and visual analysis tools.

My advice.

Trust your ears, but only up to a point. Rest them, use reference tracks, check your mixdowns on as many reproduction systems as possible, and grab your trustworthy spectral analyser to keep an eye on those hard to monitor bass tones and rogue ringing frequencies.

If you don't have one, take a look here: My recommendation Plugins for Audio Production

(Q&A Clarify Version)

"EQ are not easy as it look. A proper EQ can make or When it's not proper... can break a tracks"

"The common misconception that you should high pass all of your tracks except the kick and the bass."

Q: Apply High Pass Filter on the track that doesn't need Low end, isn't that make sense?

A: EQ isn't so simple as it look, Because every filters introduce phase shifting into your signal, It's affected the phase coherence.

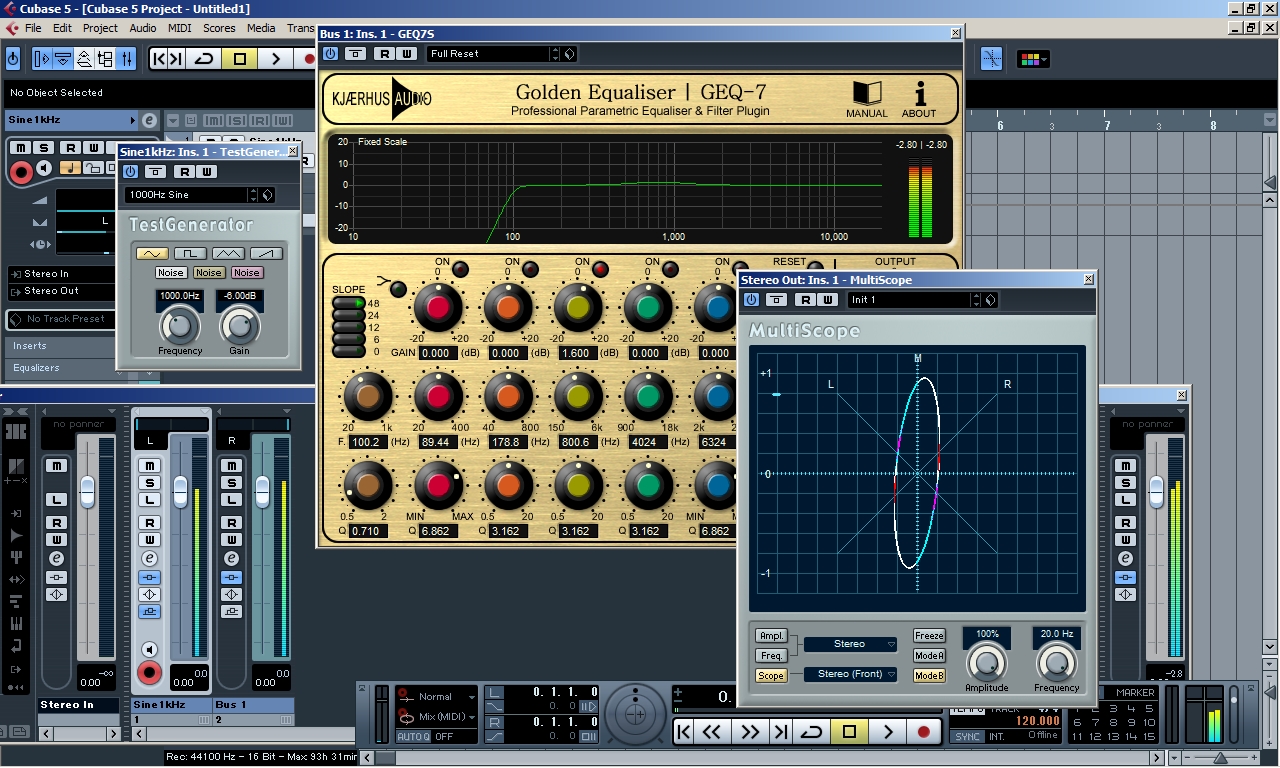

The Setup

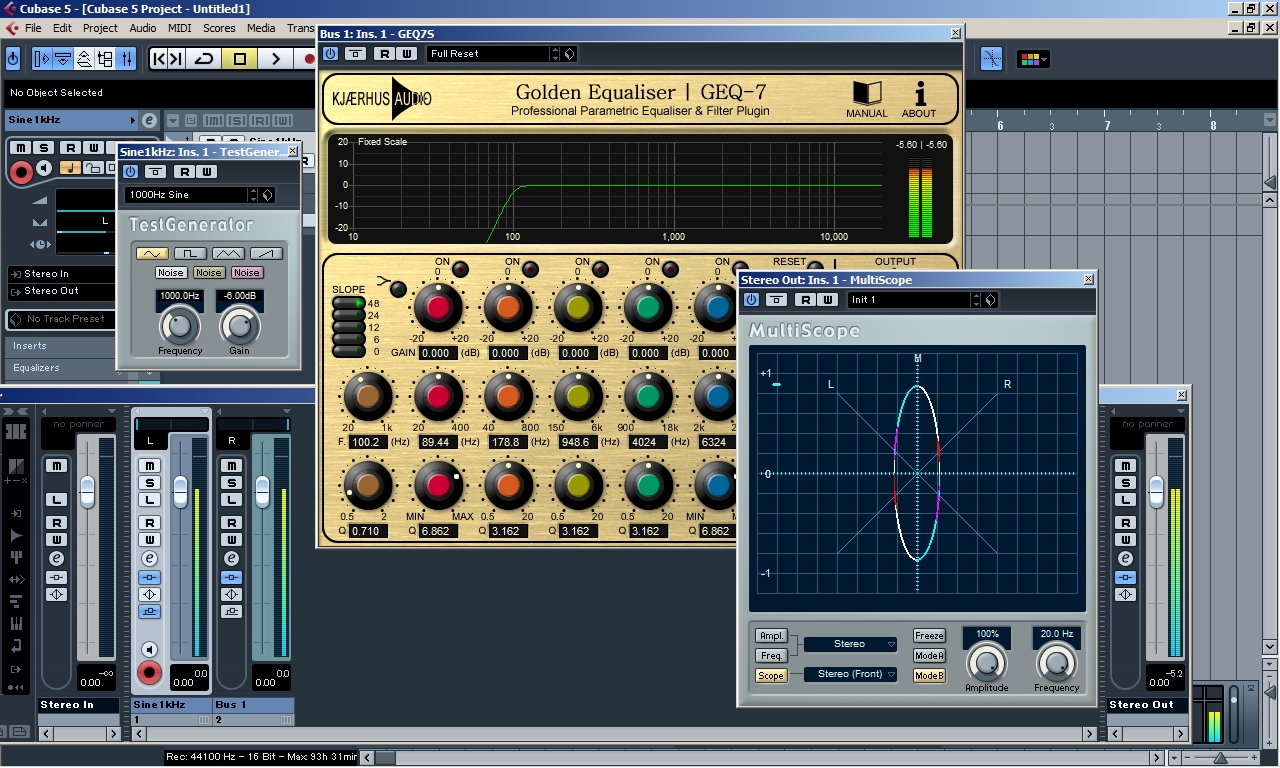

I create the audio track and use tone generator to generate sine wave at 1kHz and then Pan to the Left. And send this audio track to the buss channel that Pan to the Right to simulate the real mixing scenario (Stereo). The Left and Right are sound Exactly the same. Then i insert the Phase meter on the Output channel (master channel) so we can see the behavior of phase coherence between those two tracks.

As we can see there is no Phase correlation, You can call it "Digitally Perfect".

In theory. HPF at 100Hz. shouldn't affect the sound at 1kHz at all, Because 100Hz HPF and 1kHz is too far away from each other right? Let's see if this is true.

As we can see on the Phase meter. There is in fact something changing. It's not much but it is something.

Keep in mind this is just a shallow filter (12db/oct)

There you have it at 48db/oct filter. A 1kHz Sinewave is being affected by High-Pass Filter at 100Hz.

The result is sound the same... Yes of course. It's not affected the sound, But it affected the phase coherency.

This is actually how the filter work "There is always some phase shifting happening when using a filter" The more steep of the filter, The stronger effect of phase shifting become.

Q: Normal bell EQ does not affected from phase shifting?

A: No. The Bell EQ actually is just a 2 filter combine, No matter what cut or boost.

As we can see. I use bell EQ curve to boost frequency at 800Hz only a few dB and phase start to loss the balance.

and turn toward Right channel.

Q: Ok, We got the phase shift and we got another phase shift on every channel, That shouldn't matter right?

A: Not completely. EQ doesn't linearly affected the same way. Which mean if i start to sweeping frequency inside tone generator around, The spectrum of phase linearity start to drift around as well.

(Example of phase drift in the picture below)

As I expected. Because of the way the filter works.

This is something to keep in mind next time you adding High-Pass Filter.

Q: So, I just using Linear Phase EQ to compensate for that and it should be fine?

A: It's doesn't work that easy, Because Linear Phase EQ can give you more problem than it solved the problem.

I will explain about Linear Phase EQ, But that's something for different Audio Myths-Busting episode.

Conclusions (If you read all of this, Please don't take everything too serious)

- Don't do HPF by default, is like a blindly fix something that's not gonna work.

- If you high pass your tracks too much, you lose a lot of the low end energy in your mix and the highs make it sound harsh and brittle. You're basically taking away the balls of the track. Try attenuating the lows (perhaps with a shelf) instead of cutting them.

- Because filters introduce phase shifts into your signal, you're creating phase problems which build up in the mix between certain elements - especially if your're high passing multi-tracks instruments separately. Therefore if you must high pass such instruments, high pass them together at the bus stage.

- Because of the resonant bump (regardless of visual of EQ show to you) at the cutoff point of a pass filter, don't high pass all of your tracks at the same frequency. For instance, if you're cutting all of your tracks at 80Hz, you're going to get a build up around 80Hz.

"EQ are not easy as it look. A proper EQ can make or When it's not proper... can break a tracks"

"The common misconception that you should high pass all of your tracks except the kick and the bass."

Q: Apply High Pass Filter on the track that doesn't need Low end, isn't that make sense?

A: EQ isn't so simple as it look, Because every filters introduce phase shifting into your signal, It's affected the phase coherence.

The Setup

I create the audio track and use tone generator to generate sine wave at 1kHz and then Pan to the Left. And send this audio track to the buss channel that Pan to the Right to simulate the real mixing scenario (Stereo). The Left and Right are sound Exactly the same. Then i insert the Phase meter on the Output channel (master channel) so we can see the behavior of phase coherence between those two tracks.

As we can see there is no Phase correlation, You can call it "Digitally Perfect".

In theory. HPF at 100Hz. shouldn't affect the sound at 1kHz at all, Because 100Hz HPF and 1kHz is too far away from each other right? Let's see if this is true.

As we can see on the Phase meter. There is in fact something changing. It's not much but it is something.

Keep in mind this is just a shallow filter (12db/oct)

There you have it at 48db/oct filter. A 1kHz Sinewave is being affected by High-Pass Filter at 100Hz.

The result is sound the same... Yes of course. It's not affected the sound, But it affected the phase coherency.

This is actually how the filter work "There is always some phase shifting happening when using a filter" The more steep of the filter, The stronger effect of phase shifting become.

Q: Normal bell EQ does not affected from phase shifting?

A: No. The Bell EQ actually is just a 2 filter combine, No matter what cut or boost.

As we can see. I use bell EQ curve to boost frequency at 800Hz only a few dB and phase start to loss the balance.

and turn toward Right channel.

Q: Ok, We got the phase shift and we got another phase shift on every channel, That shouldn't matter right?

A: Not completely. EQ doesn't linearly affected the same way. Which mean if i start to sweeping frequency inside tone generator around, The spectrum of phase linearity start to drift around as well.

(Example of phase drift in the picture below)

As I expected. Because of the way the filter works.

This is something to keep in mind next time you adding High-Pass Filter.

Q: So, I just using Linear Phase EQ to compensate for that and it should be fine?

A: It's doesn't work that easy, Because Linear Phase EQ can give you more problem than it solved the problem.

I will explain about Linear Phase EQ, But that's something for different Audio Myths-Busting episode.

Conclusions (If you read all of this, Please don't take everything too serious)

- Don't do HPF by default, is like a blindly fix something that's not gonna work.

- If you high pass your tracks too much, you lose a lot of the low end energy in your mix and the highs make it sound harsh and brittle. You're basically taking away the balls of the track. Try attenuating the lows (perhaps with a shelf) instead of cutting them.

- Because filters introduce phase shifts into your signal, you're creating phase problems which build up in the mix between certain elements - especially if your're high passing multi-tracks instruments separately. Therefore if you must high pass such instruments, high pass them together at the bus stage.

- Because of the resonant bump (regardless of visual of EQ show to you) at the cutoff point of a pass filter, don't high pass all of your tracks at the same frequency. For instance, if you're cutting all of your tracks at 80Hz, you're going to get a build up around 80Hz.

(Technical Explain) Please read Audio Myths-Busting EP.4 Before EP.5 for better understanding.

Linear phase EQ vs. regular EQ

Describing linear phase EQ without getting too technical is somewhat difficult. It helps, however, to first draw a distinction between “regular” EQ and linear phase EQ.

Regular EQ is the tool that alters the frequencies present in any given track. When these frequencies are manipulated, something called “phase shifting” occurs. In the old days of analog EQing, this shifting was an electrical response involving capacitors and inductors. The digital EQ of today simply mimics this physical alteration.

In the analog world, phase smear was just something that product designers tried to minimize or mold into something that sounded pleasing. In the digital world, all bets are off. When plugin coding and processing power started to become more advanced, developers realized they could finally do what engineers have wanted to do this whole time. Linear phase equalizers are impossible in the analog world, but in plugin land anything is possible. Linear Phase EQ is equalization that does not alter the phase relationship of the source— the phase is entirely linear.

The irony of Linear Phase EQs is that they were initially conceived because of an engineers desire to eliminate phase smearing, which was thought to be a negative byproduct of using analog hardware equalizers. Once software programmers were able to develop a Linear Phase EQ, they soon realized that there were new problems and artifacts to overcome.

When should i use Linear Phase EQs?

Linear phase EQ can be a useful tool in situations where an audio source is heard on more than one track. Some examples of this are:

1. Using linear phase EQ can be useful when you are processing an audio source with multiple microphones on it

An obvious example of this would be drums. Even with gating and other plugins in place to isolate each drum, there will still be some bleed from other drums coming into each microphone.

The kick drum will get into the snare mic, the snare into the tom mics, etc. Adjusting the phase relationships between all the microphones with EQ could affect the sound of the drum kit quite drastically. This where using linear phase EQ could come in handy. You can make the adjustments you want without causing any phase smearing among the other drum mics.

2. Stereo Tracks

Linear phase EQ could also be useful for any instruments recorded in stereo, such as acoustic guitars. In the recording process, these mics are placed carefully so that they are in phase and capture the most accurate stereo image possible.

Adjusting the phase relationship between the two mics with EQ could affect the tone of the guitars in undesirable ways. Again, linear phase EQ would allow you to make the necessary adjustments without affecting the relationship between the two microphones.

3. Parallel Processing

Linear phase EQ could be useful in parallel processing chains, such as parallel compression or distortion. Adjusting the phase relationship between the source audio and the parallel processed audio could alter the tone of the track in unintended ways. Using linear phase EQ here would ensure that this doesn’t happen.

Other uses

Linear phase EQ can also be useful when making very narrow boosts or cuts. With minimum phase EQ, the degree of phase shifting is greater as your EQ curve becomes steeper in slope.

Using linear phase EQ for these adjustments can prevent more phase smearing from happening due to a narrow boost or cut. This is why some mastering engineers like using them in their workflow. The mastering process often involves making minute EQ adjustments to a mix.

Linear phase EQs give the mastering engineer the ability to make those adjustments without worrying about how the phase shift will affect the rest of the mix.

Obvious downsides of Linear Phase EQ

Linear phase EQ may sound like a great tool so far, but there are some downsides you should consider before throwing it all over your mixes.

CPU and Latency issue

Linear phase EQs use a higher amount of CPU than minimum phase EQs do. If you use too many of them, your DAW will run very slowly.

Latency may also become an issue when using too many linear phase EQs , causing delays in your tracks when they are played back. Any plugins used on your tracks will delay them by a certain amount of samples. Most DAWs have a delay compensation feature to avoid latency issues. This delays all tracks by the same amount of samples so that they will all play back at the same time.

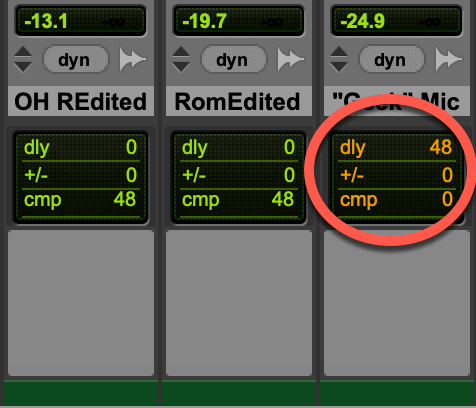

An Example of delay compensation in Pro Tools

Even with this feature in place, linear phase EQs can push the limits of your DAW’s delay compensation. Linear phase EQs can delay a track anywhere from 3,000 to 20,000 samples. If you are working in Pro Tools, for example, there is a limit of 16,000 samples at a sample rate of 44.1 kHz. You do get a higher limit if you increase the sample rate of your session, but linear phase EQs can still take up a hefty amount of it.

If you want to use linear phase EQ in your mixes, it is best to use them when you have a specific need for them, such as the ones discussed in this article. That way you can avoid taxing your CPU and eliminate any undesirable latency.

Pre-ringing

Pre-ringing is a negative artifact commonly associate with using Linear Phase EQs which affects the initial transient. Instead of starting with a sharp transient there is a short but often audible crescendo in the waveform before the transient hits. The pre-ringing is a resonance similar to a reverse reverb that you might hear before your audio begins. It is actually the sound of the EQ shifting the phase of the entire signal. Since it happens before the transient, it sounds very unmusical and displeasing. This affects the overall tonality of transients which people do not find desirable.

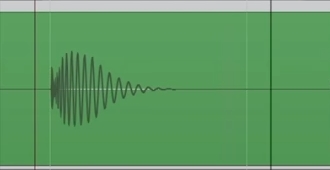

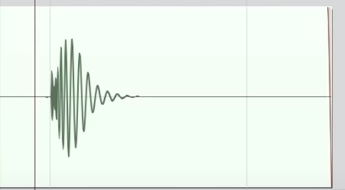

Kick drum before Linear Phase EQ Processing.

Kick drum after Linear Phase EQ Processing.

They are not sound wrong but sound different also the sustain (tail) of kick drum sound is getting short than original.

This is what Pre-ringing artifact look like.

In order to make the Low-end Phase coherence, it's need to adjust the low end that far off to the front of original Transient.

Pre-ringing artifact is a natural side-effect of Linear Phase EQ, and this side effect can get you in to the scenario at which your kick drum won't impact as much anymore, and this is because the low-end is already start before the attack of the kick drum. It's change a lot in your sound in order to get that linearity in phase response.

It takes a lot of processing power to do this as we discussed, so you will audibly hear the shift as pre-ring because it does not happen instantaneously. It is more noticeable if there are a lot of transients in a track. For example, you might notice a low-end ringing right before a kick drum transient.

Can you get rid of Pre-ringing?

Unfortunately. There is no way to completely get rid of Pre-ringing. This is the price you must pay to get access to "Unnatural EQ"

There are ways to make it less audible in your mix if you need to use a linear phase EQ. Here are a few tips you can try:

Avoid extreme boosts

The more you boost a frequency, the greater the amplitude of the pre-ring. Cutting frequencies makes pre-ringing less audible than boosts. If you are going to boost frequencies with linear EQ, try to only make minor boosts of a few dB.

Focus on adjusting high frequencies (if possible)

While the amplitude of the pre-ring is constant across the frequency spectrum, the duration of it shortens as you go higher in frequency. If you can, try to use linear phase EQs to adjust higher frequencies to avoid excessively long pre-ringing. If you cannot do this, go for more subtle boosts in the low end.

Pay attention to your EQ curve

The relationship between pre-ringing and EQ curves, or Q value, is complex. A narrow Q value will increase the duration of pre-ringing, but reduce the amplitude of it, and vice versa when the Q value is widened.

There is not really an ideal scenario here, so it is best to experiment with the Q value to see what gives you the best sound.

Lack of "color"

As we discussed earlier, sometimes the phase shifts that come from using minimum phase EQs create a desirable sound that we want in our mixes. This “coloration” is something you cannot get with linear phase EQ.

Linear EQ tends to create a precise, digital sound that is too unnatural. The imperfections in analog gear are actually quite desirable for many musicians. Many feel that analog gear imparts an organic or human-like quality on audio.

Conclusions

As we can see, there are pros and cons to both types of equalizers. Minimum phase EQs can add a nice character to your tracks, but the phase shifting that occurs can damage the relationship between tracks if you are working with stereo or multiple mic sources.

Linear phase EQs can help keep the phase relationship intact in these situations but can take up a lot of CPU, cause latency issues and introduce unwanted resonances from pre-ringing.

As with anything in music production, there is no one size fits all solution. Both types of equalizers are good tools to have for different reasons.

Ultimately, if you have both, you will have to experiment with them in your mixes and use your ears to decide which type serves your tracks best. If you do not have a linear phase EQ, remember that plenty of great records have been made with good ol’ fashioned equalization, so don’t fret. Ultimately, linear phase EQ is not needed for good mixes, but it certainly makes mixing easier when you need it.

Linear phase EQ vs. regular EQ

Describing linear phase EQ without getting too technical is somewhat difficult. It helps, however, to first draw a distinction between “regular” EQ and linear phase EQ.

Regular EQ is the tool that alters the frequencies present in any given track. When these frequencies are manipulated, something called “phase shifting” occurs. In the old days of analog EQing, this shifting was an electrical response involving capacitors and inductors. The digital EQ of today simply mimics this physical alteration.

In the analog world, phase smear was just something that product designers tried to minimize or mold into something that sounded pleasing. In the digital world, all bets are off. When plugin coding and processing power started to become more advanced, developers realized they could finally do what engineers have wanted to do this whole time. Linear phase equalizers are impossible in the analog world, but in plugin land anything is possible. Linear Phase EQ is equalization that does not alter the phase relationship of the source— the phase is entirely linear.

The irony of Linear Phase EQs is that they were initially conceived because of an engineers desire to eliminate phase smearing, which was thought to be a negative byproduct of using analog hardware equalizers. Once software programmers were able to develop a Linear Phase EQ, they soon realized that there were new problems and artifacts to overcome.

When should i use Linear Phase EQs?

Linear phase EQ can be a useful tool in situations where an audio source is heard on more than one track. Some examples of this are:

1. Using linear phase EQ can be useful when you are processing an audio source with multiple microphones on it

An obvious example of this would be drums. Even with gating and other plugins in place to isolate each drum, there will still be some bleed from other drums coming into each microphone.

The kick drum will get into the snare mic, the snare into the tom mics, etc. Adjusting the phase relationships between all the microphones with EQ could affect the sound of the drum kit quite drastically. This where using linear phase EQ could come in handy. You can make the adjustments you want without causing any phase smearing among the other drum mics.

2. Stereo Tracks

Linear phase EQ could also be useful for any instruments recorded in stereo, such as acoustic guitars. In the recording process, these mics are placed carefully so that they are in phase and capture the most accurate stereo image possible.

Adjusting the phase relationship between the two mics with EQ could affect the tone of the guitars in undesirable ways. Again, linear phase EQ would allow you to make the necessary adjustments without affecting the relationship between the two microphones.

3. Parallel Processing

Linear phase EQ could be useful in parallel processing chains, such as parallel compression or distortion. Adjusting the phase relationship between the source audio and the parallel processed audio could alter the tone of the track in unintended ways. Using linear phase EQ here would ensure that this doesn’t happen.

Other uses

Linear phase EQ can also be useful when making very narrow boosts or cuts. With minimum phase EQ, the degree of phase shifting is greater as your EQ curve becomes steeper in slope.

Using linear phase EQ for these adjustments can prevent more phase smearing from happening due to a narrow boost or cut. This is why some mastering engineers like using them in their workflow. The mastering process often involves making minute EQ adjustments to a mix.

Linear phase EQs give the mastering engineer the ability to make those adjustments without worrying about how the phase shift will affect the rest of the mix.

Obvious downsides of Linear Phase EQ

Linear phase EQ may sound like a great tool so far, but there are some downsides you should consider before throwing it all over your mixes.

CPU and Latency issue

Linear phase EQs use a higher amount of CPU than minimum phase EQs do. If you use too many of them, your DAW will run very slowly.

Latency may also become an issue when using too many linear phase EQs , causing delays in your tracks when they are played back. Any plugins used on your tracks will delay them by a certain amount of samples. Most DAWs have a delay compensation feature to avoid latency issues. This delays all tracks by the same amount of samples so that they will all play back at the same time.

An Example of delay compensation in Pro Tools

Even with this feature in place, linear phase EQs can push the limits of your DAW’s delay compensation. Linear phase EQs can delay a track anywhere from 3,000 to 20,000 samples. If you are working in Pro Tools, for example, there is a limit of 16,000 samples at a sample rate of 44.1 kHz. You do get a higher limit if you increase the sample rate of your session, but linear phase EQs can still take up a hefty amount of it.

If you want to use linear phase EQ in your mixes, it is best to use them when you have a specific need for them, such as the ones discussed in this article. That way you can avoid taxing your CPU and eliminate any undesirable latency.

Pre-ringing

Pre-ringing is a negative artifact commonly associate with using Linear Phase EQs which affects the initial transient. Instead of starting with a sharp transient there is a short but often audible crescendo in the waveform before the transient hits. The pre-ringing is a resonance similar to a reverse reverb that you might hear before your audio begins. It is actually the sound of the EQ shifting the phase of the entire signal. Since it happens before the transient, it sounds very unmusical and displeasing. This affects the overall tonality of transients which people do not find desirable.

Kick drum before Linear Phase EQ Processing.

Kick drum after Linear Phase EQ Processing.

They are not sound wrong but sound different also the sustain (tail) of kick drum sound is getting short than original.

This is what Pre-ringing artifact look like.

In order to make the Low-end Phase coherence, it's need to adjust the low end that far off to the front of original Transient.

Pre-ringing artifact is a natural side-effect of Linear Phase EQ, and this side effect can get you in to the scenario at which your kick drum won't impact as much anymore, and this is because the low-end is already start before the attack of the kick drum. It's change a lot in your sound in order to get that linearity in phase response.

It takes a lot of processing power to do this as we discussed, so you will audibly hear the shift as pre-ring because it does not happen instantaneously. It is more noticeable if there are a lot of transients in a track. For example, you might notice a low-end ringing right before a kick drum transient.

Can you get rid of Pre-ringing?

Unfortunately. There is no way to completely get rid of Pre-ringing. This is the price you must pay to get access to "Unnatural EQ"

There are ways to make it less audible in your mix if you need to use a linear phase EQ. Here are a few tips you can try:

Avoid extreme boosts

The more you boost a frequency, the greater the amplitude of the pre-ring. Cutting frequencies makes pre-ringing less audible than boosts. If you are going to boost frequencies with linear EQ, try to only make minor boosts of a few dB.

Focus on adjusting high frequencies (if possible)

While the amplitude of the pre-ring is constant across the frequency spectrum, the duration of it shortens as you go higher in frequency. If you can, try to use linear phase EQs to adjust higher frequencies to avoid excessively long pre-ringing. If you cannot do this, go for more subtle boosts in the low end.

Pay attention to your EQ curve

The relationship between pre-ringing and EQ curves, or Q value, is complex. A narrow Q value will increase the duration of pre-ringing, but reduce the amplitude of it, and vice versa when the Q value is widened.

There is not really an ideal scenario here, so it is best to experiment with the Q value to see what gives you the best sound.

Lack of "color"

As we discussed earlier, sometimes the phase shifts that come from using minimum phase EQs create a desirable sound that we want in our mixes. This “coloration” is something you cannot get with linear phase EQ.

Linear EQ tends to create a precise, digital sound that is too unnatural. The imperfections in analog gear are actually quite desirable for many musicians. Many feel that analog gear imparts an organic or human-like quality on audio.

Conclusions

As we can see, there are pros and cons to both types of equalizers. Minimum phase EQs can add a nice character to your tracks, but the phase shifting that occurs can damage the relationship between tracks if you are working with stereo or multiple mic sources.

Linear phase EQs can help keep the phase relationship intact in these situations but can take up a lot of CPU, cause latency issues and introduce unwanted resonances from pre-ringing.

As with anything in music production, there is no one size fits all solution. Both types of equalizers are good tools to have for different reasons.

Ultimately, if you have both, you will have to experiment with them in your mixes and use your ears to decide which type serves your tracks best. If you do not have a linear phase EQ, remember that plenty of great records have been made with good ol’ fashioned equalization, so don’t fret. Ultimately, linear phase EQ is not needed for good mixes, but it certainly makes mixing easier when you need it.