So I've been making good on my goal of going through some music theory textbooks. I've gotten through the notation stuff and have arrived at the major scales.

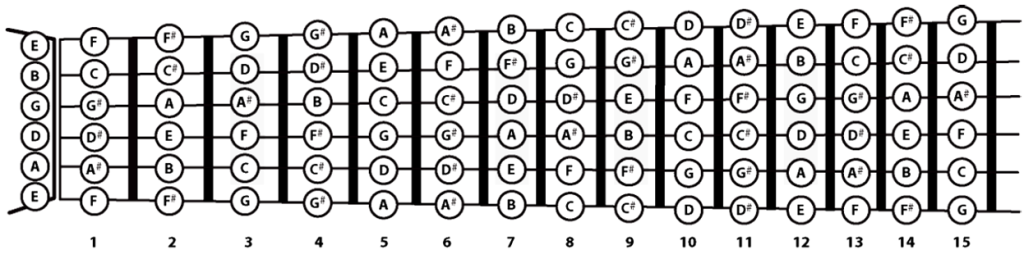

As per my book, notes are separated by half and whole steps, which are 1 and 2 keys apart on the piano, respectively.

The major scale is composed of 2 tetrachords, which are each four notes in a pattern of whole step, whole step, half step. The tetrachords have a whole step between them. A scale can begin on any note.

"Great," I'm thinking. "So theoretically, as long as you know the pattern, you can start on any note and generate a new major scale."

That works, I think, just working up the note names on the staff, which line up with the white keys. But then, unless you have a keyboard in front of you, how do you know where the black keys fall?

It seems like there must be some deeper meaning behind whole/half steps that gives rise to the particular placements of the black keys, since there isn't a black key between every 2 white keys. (Something a piano maker would surely have to have known before the piano was invented.) Does anyone know what that reason is?

As per my book, notes are separated by half and whole steps, which are 1 and 2 keys apart on the piano, respectively.

The major scale is composed of 2 tetrachords, which are each four notes in a pattern of whole step, whole step, half step. The tetrachords have a whole step between them. A scale can begin on any note.

"Great," I'm thinking. "So theoretically, as long as you know the pattern, you can start on any note and generate a new major scale."

That works, I think, just working up the note names on the staff, which line up with the white keys. But then, unless you have a keyboard in front of you, how do you know where the black keys fall?

It seems like there must be some deeper meaning behind whole/half steps that gives rise to the particular placements of the black keys, since there isn't a black key between every 2 white keys. (Something a piano maker would surely have to have known before the piano was invented.) Does anyone know what that reason is?